Interview with Freeman Patterson

About Freeman Patterson...

Freeman Patterson lives at Shamper's Bluff, New Brunswick, near his childhood home. He attended multi-grade (one-room) schools in Grey's Mills and Long Reach, and high school at Macdonald Consolidated School in Kingston. He graduated with a B.A. (Honours: Philosophy) from Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, in 1959. The subject of his honour's thesis was "The Form Of The Good" in Plato's Republic. In 1962 he received a Master of Divinity degree (M. Div.) from Union Theological Seminary at Columbia University, New York. His master's thesis was Still Photography As A Medium Of Religious Expression. While in New York, Freeman studied photography and visual design privately with Dr. Helen Manzer.

From 1962 to 1965 Freeman was dean of religious studies at Alberta College, Edmonton, and began actively to work in photography. He moved to Toronto in 1966 to work for one year at Berkeley Studio, the United Church of Canada still photography and film production house. During this time and until the late 1970's, Freeman completed numerous assignments across Canada for the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board of Canada. He also developed a large roster of professional clients in the editorial and advertising fields. Freeman has always been a strong supporter of the amateur photography community, and is a life member and former president of The Toronto Guild for Colour Photography.

Freeman returned to New Brunswick in 1973 primarily in order to pursue his personal artistic interests and to establish a workshop of photography and visual design. Since then he has taught several week-long classes every year and, commencing in 1984, in southern Africa as well, where he co-founded the Namaqualand Photographic Workshops. He has given numerous workshops in the United States, Israel, New Zealand and Australia.

Although Freeman does much of his photographic work at home, he travels widely to photograph and to teach. Since 1973 he has frequently presented half-day and all-day seminars to large groups (50 to 4000 persons) in the visual arts, music, education, and ecology across Canada, the United States, and in other countries. Since 1977 he has written and illustrated four instructional books on photography and visual design and has co-authored a fifth, four large cloth-edition books, and co-authored and illustrated two more. In 1996 he completed a CD-ROM entitled Creating Pictures: A Visual Design Workshop and a major retrospective book of text and photographs, entitled ShadowLight: A Photographer's Life for Harper Collins of Canada which was followed in 1998 by Odysseys: Meditations and Thoughts For A Life's Journey and in 2003 by The Garden. Freeman has written for various magazines, CBC radio, and been featured on CBC television's Man Alive, Sunday Arts And Entertainment, and Adrienne Clarkson Presents.From 1973 to 1989, Freeman was an elected trustee of New Brunswick School District #19, served for eight years as vice-president and director of Masterfile (a major stock photography agency), two years on the board of Aids Saint John, and six years as a trustee of the Nature Conservancy of Canada. He has donated his property on Shamper's Bluff to the conservancy for an ecological reserve and education area. An avid motorcyclist, he is also a member of the Saint John Harley Owners' Group.

To learn more about Freeman Patterson please visit his website

1. Freeman, thank you so much for your time. How and why did you get into nature photography?

You’re very welcome, Mario. I appreciate your invitation.

First of all, though, I’d like to say that I don’t regard myself primarily as a nature photographer, but rather as a photographer who chooses many natural things and situations as subject matter, especially botanical and landscape material.

I have always had an emotional affinity to the plant world, which developed when I was a child growing up in rural eastern Canada. Because I was the only child of my age in the community, my best friends were the forests, the fields, the river and its beaches, all of which I explored in every season of the year. Although many of my nature images are documentary, a large proportion are not.

Because of my emotional connection with the natural world, I also endeavour to convey my personal response through interpretive imagery of natural things.

2. Namaqualand is your second home where you love photographing the amazing displays of spring flowers and you recently returned from your 36th Namaqualand / Southern Namibia trip! What draws you back year after year?

Well, it certainly was the amazing annual display of spring flowers that drew me to Namaqualand in the first place and one of the reasons I keep returning year after year. I can never experience too much of this incredible, fleeting beauty. Even poor years, which are very few indeed, are spectacular somewhere. However, I also return frequently during February and March and to explore the coastal areas and both the Richtersveld and Namibia to the north.

Namibia and Namaqualand (parts of which are also extremely desert-like) could scarcely be less like my Canadian home, where Earth is always clothed with vegetation or snow or clouds. In Namaqualand and especially in the Namib one sees Earth’s bones, the land stripped naked. Then, when the rains come, transformation!

However, the seemingly barren, stripped-down landscape of gigantic boulders and rocky or sandy veld affects me in a primal way. Every time I return to the Richtersveld, I have the overpowering feeling of coming home. In fact, the first time that I ever went there I had an immediate “deja vue” experience, knowing in detail what lay on the other side of huge boulders before I walked around them.

Here and elsewhere in the southern Namib change occurs so slowly that I often feel this afternoon could have been two million years ago or it could be two million years in the future. In other words, the mountain desert utterly alters my experience of time. In fact, as nowhere else I’ve ever been on the planet, I “feel” eternity.

I also return to Namaqualand because of the friends I have made there.

3. Do you use any 'exotic' lenses such as extreme wide-angles or tilt/shift lenses for your macro or landscape images?

No! In fact, I have never owned a lens longer than 300mm or shorter than 17mm. I have a 100mm macro. Equipment per se doesn’t interest me. I only purchase something when I can’t get by without it.

Having said that I must add that I use a tripod for 95% of my photography, not just because a tripod holds a camera steady, but because it is essential to care and discipline. (I own five identical tripods, the Manfrotto 190 – one is in my house, one in my car, one in my truck or bakkie, one in South Africa, and one in New Zealand.)

The tripod is every bit as useful for digital photography as for film. I believe in respecting my first tools – my eyes and my camera. If I use them thoughtfully, which a tripod enables me to do, I usually have next to nothing to do on the computer, which is a very poor place to stay healthy and keep fit.

4. Most interviews of professional photographers tend to focus on the person's equipment but I think that we both agree on the fact that quality photo gear is important but there are other criteria that are just as important in being able to make good photographs. What are these other skills that a person should be cultivating if he/she would like to produce quality images?

Because photography is a visual medium, a strong working knowledge of visual design is essential. That’s just as true for reportage as it is for architectural imagery or nature photography. Our ability to communicate with words in any language depends completely on our knowledge of the building blocks of the language and how to arrange and re-arrange them to communicate our thoughts and feelings.

It’s exactly the same with pictures; one must know the building blocks of visual design and the various principles for arranging them (composition). I am not talking about “rules,” which are deadly for creative thought and are only for people who choose not to think for themselves.

5. Your books seem to be less about photographic technique and much more about 'visual design' and creativity. Some people think that professional photographers are born with creativity and imagination - you would disagree with that statement wouldn't you?

Yes, I definitely disagree! Everybody is born with more creative potential than she or he can ever begin to use. Our problem is never a lack of creativity, but a willingness to utilize what we have.

I love giving myself (and others) personal assignments such as rolling a hoola hoop and then, wherever it falls over, standing inside the circle and making a minimum of 30 good compositions looking out – without repeating myself. After making about 15 photographs the going gets rough, and between compositions 16 and 20 I seem to be bashing my head against a wall, but then almost miraculously the scales seem to drop from my eyes and I sail off into new visual dimensions.

I also deliberately tackle material I dislike or find utterly boring, perhaps a dark green or black garbage or rubbish bag, a white plastic chair, or a messy plate after somebody has eaten a breakfast of bacon and eggs. I may not get any masterpieces from these exercises, but I certainly sharpen my visual acuity.

6. In your book 'Photography and the Art of Seeing' you discuss a few barriers to photographers being able to 'see'. One of the barriers is the camera because it does not see as the human eye does. Please can you expand on that.

Humans tend to view the world as if they were looking through the viewfinder with a 50mm lens attached to the camera. That’s why the 50mm used to be called a “standard” lens. Like many barriers to new thinking and seeing this one remains a barrier only as long as you regard it as one. So, treat a liability as if it were an asset and you’ll turn it into one.

For me, one of the best approaches to getting out of a rut is to regard it an opportunity. For example, if you’re stuck in the mud, say “Whow, look at all the mud! What a fabulous opportunity!” By pretending you’re a bird, for instance, you can imagine yourself gliding over this broad, brown, textured landscape that’s criss-crossed with streams and pools. You can make a lot of very good “aerial photographic images” by using your imagination and a 50mm lens with even a small expanse of mud.

A wide-angle or telephoto lens does not provide a “standard” view of the world, and you must work with them until you can previsualize how things will appear when using them.

I have observed over the years that virtually all photographers, on their own, fail to discover how to use a wide-angle lens effectively. Usually, it’s because they regard the lens as enabling them to include more in the picture when standing close to the area being photographed, but completely fail to appreciate that it is their most valuable technical tool in establishing a real sense of perspective on a flat surface.

Of course, if they have had training in visual design, particularly in how the deformation of space causes us to see perspective in both our three-dimensional world and in our two-dimensional images, they are more likely to catch on fast.

7. In your book 'Photographing the World Around You' you compare linguistic design to visual design and you go on to discuss how people should arrange the various 'building blocks' of visual design so that their photograph adequately expresses what they saw. Is your goal here to show people that they need to ensure the relationship between the two sides of their brain remains strong but with the emphasis on constantly developing the right brain?

I’ve already talked about this, but should add that craft always precedes art. You have to do all the necessary left-brain work until the details of a craft become automatic, which is when you stop thinking about them and are just doing what you set out to do.

A good comparison is to learning a new language. You study and practice (often slow and painful at first) until gradually you begin to understand and talk a little faster, then a little faster still, and then the whole process really speeds up until one day you find you are chatting away in the language effortlessly. You have converted from left-brain to right-brain activity, even though you can immediately switch back to using your left brain when you want to choose your words very carefully for some specific reason.

For example, in all visual media you have to be aware of what the three basic orientations of a line make a viewer sense or feel in order to orient a line or lines in a picture in the way that will communicate the feeling you want. To achieve an automatic sense of what lines – their direction, width, length, intensity, and orientation – convey takes study and practice.

8. In your book 'Photo Impressionism and the Subjective Image' you show how photographs can be used to alter physical reality (for example by shooting multiple exposures and intimate Earthscapes) in order to express the photographer's feelings to specific subjects. Do you think people are afraid to experiment and try new things, as we have been taught to 'stick to the rules!' and this stifles our creativity and we end up with boring, unoriginal shots?

Experimenting always involves risk. When photographers try to make images for somebody else – judges in a camera club, for example – rather than for themselves, what they are doing is letting their ego get in the way of their photography. Make pictures that matter to you, and if you learn to do that well, you will end up pleasing or stimulating others in the process.

9. We hear about the Five-P's that together make a successful photographer - Purpose, Patience, Practice, Preparation and Passion. If a photographer is passionate about creation and photography don't you think the other four P's will automatically fall into place and the person will make more creative photographs?

Of course! However, I’m not sure about the order.

10. I have read on some forums that the creative nature photography principles that you teach are best suited to macro and landscape photography but not to bird or wildlife photography. Would you agree with that statement?

Definitely not! As I’ve noted elsewhere, the building blocks and principles of visual design are universal. To move away from nature briefly, I’ve made a lot of photographs of bikers and biking (being an avid motorcycle rider for many years) and I’ve also made thousands of macro images of light shining through glass.

When I am composing images of these subjects, just as with red hartebeest, springbok, or fish eagles I am depending on precisely the same visual building blocks and the same range of principles for arranging them in picture space.

11. Let's chat about your photo workshops for a minute – please give us an idea of a typical day on one of them.

The week-long workshops, which I always teach with another photographer whom I really respect, are usually limited in number to 12 participants. This enables us to give good field instruction, as each of the two field groups of six gets an instructor. We alternate daily. Also, both of us give lectures, i.e. illustrated presentations. I usually present all or most of the visual design lectures, my teaching partner tends to focus on technical matters and various camera techniques, and we share the daily evaluation sessions.

There’s nothing special about the format. Typically we do three or so hours of field work in the morning, which in my case may be anywhere, as I am a firm believer that the best place to see and make good photographs is wherever you are – in a parking lot, a field of flowers, a street corner, a rocky beach, or looking through a window pane, if it’s raining. I really couldn’t care less. If you can learn to see well in a shopping mall parking lot, then you should have no difficulty in Etosha Pan or at Sossuvlei.

Late every morning, after coffee, I usually give an hour illustrated lecture. Then comes lunch, and afterwards I crash for an hour or so (I've been doing that for 40 years). Meanwhile the workshoppers get busy downloading their images and then my teaching partner gives a lecture.

Coffee or tea comes again, then we project and evaluate publicly a few images by each participant. These are not "critique" sessions as much as they are an opportunity to identify what each photographer has done well and to indicate how she or he can improve an image visually or technically. We are constructive and see no point in being otherwise.

What’s really important to the success of the workshops is that everybody stays at the same inn. Usually we are all functioning as a close-knit family within a few hours. We share meals, swap real experiences and wild tales, explore deep feelings, laugh a lot and, of course, sometimes groan if a participant drops a lens or mislays a memory card with the best photos ever on it.

The atmosphere of the workshop is vital to its success.

This means that although we don’t have to be upscale, we must have clean, comfortable accommodation, tasty and nutritious food, and a happy, pleasant staff. Then, my teaching partner and I can do what we are there to do – to help participants see better and create more effective visual statements and impressions.

12. We have seen some people advertising online photographic courses where they promise "All you need is one lesson and in just 20 minutes you can be taking astonishing photos like a pro". Freeman, you have spent more than 40 years as a nature photographer - are there any short cuts or quick fixes to improving photography skills?

Nope! Besides, every thinking person knows better.

13. You are able to place your tripod anywhere and get a dozen good photographs - is the moral of the story that we need to make the most of our current situation and that we are surrounded by good photographic subjects no matter where we are - we just need to 'see' them?

The best place in the world to see and make good photographs is wherever you are! Every place on the planet is local to somebody and exotic to everybody else, so make use of where you happen to be. Of course, that doesn’t preclude travelling because of your interests, but it does mean that you can learn absolutely anywhere.

14. Do you also learn from and get motivated by your students?

Almost invariably I end a workshop on a “high!” That’s how motivating workshop participants are, especially when we are all interacting with each other. Even the least experienced person often makes a substantial contribution, often asking an old question in a new way that sets us all thinking or makes us wonder why we never thought of that idea or approach before. I wouldn’t be giving workshops after all these years (I started in 1973), if I didn’t love the workshop milieu and feel so motivated by my students.

15. Darwin Wiggett is renowned internationally for his photography and he gives your book 'The Photography of Natural Things' the credit for inspiring him to become a nature photographer. To quote him "I was blown away by what Freeman could do with a camera. He photographed nature the way I felt when I was in nature. I wanted to do that as well." Having published over a dozen books and taught hundreds upon hundreds of students, do you ever wonder just how many photographers have been inspired by your work?

Does the actual number really matter? Just two days ago I received a really kind and thoughtful hand-written letter from a woman whom I’ve never met, but who explained what my books have meant to the development of her work. When that happens I just feel warm inside.

16. Freeman, what are your top three creative tips for the photographer who has all the photographic gear, understands the basics of exposure, composition, etc., and he's in a wilderness area like Namaqualand or Etosha national park but he wants to get out of the cliché rut and take his photography to the next level?

This is one question that I simply cannot answer in the way you ask it, because I do not have three top creative tips, and a person shouldn’t wait until he or she is out photographing to try to get out of a rut or to raise one’s level of seeing. The process is an on-going one, or should be.

Let me put it this way. Photographers have always had a love affair with technology and as long as I’ve been around they have been talking about their equipment and about how to use it. The emphasis on “how to do it” has become even more intense with the advent of the digital age and the medium is really suffering because of this preoccupation with equipment and techniques.

It all reminds me of the guy who is forever tinkering with his motorcycle, but who never really gets to ride, never feels the cool rush of air as he descends into a valley, never smells the fragrance of roses as he cruises by an old farmhouse, and never gets to watch the sun rising out of a misty ocean. No, he’s too busy deciding which tyres will provide the best traction, whether or not the muffler should be replaced, and when the handlebars are at precisely the right height and angle to give a real macho impression. If the guy is getting his kicks out of being a mechanic, that’s fine, but he’s not a biker and shouldn’t call himself one.

Equipment and technique freaks aren’t photographers either. They’re technicians. What I’m saying is that getting out of a rut requires a shift of focus from photographic hardware and software to considering thoughtfully why you are doing what you are doing. Why are you in the wilderness anyway? What does it do for you? Are you escaping from work, family, your daily life? Or, are you there because what lives and happens in wilderness stirs your soul? If you want to get out of a rut, then it’s important to stop obsessing about “how to do it” and to start considering “why you do it,” to start asking seriously what really matters to you.

If and when you can answer that question, you will find that you are no longer in a rut.

17. Any new workshops or projects that you are working on that you can tell us about?

Well, yes! Eighteen months ago I decided that, as a Canadian living in eastern Canada, my being unable to speak French was both a form of insensitivity and a kind of self punishment.

I also wanted to prove that you can learn a language at any age. So, with two sentences of French in my vocabulary (“Je ne parle pas le français. Je viens d’apprendre.” I do not speak French. I am coming to learn), I drove out of New Brunswick, the province in which I live, to a three-week French immersion program in neighbouring Quebec. It was quite scary for me, although for years I had been unafraid to stand in front of South African audiences and make a fool of myself in Afrikaans. I am still far from fluent in French, but I am now functional in the language and going for fluency. It’s been damn hard work, but extremely rewarding.

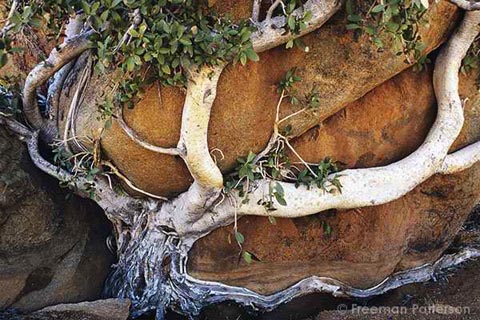

However, more important for me as a photographer are two on-going projects. The first has lasted 20 years now because it matters to me deeply on both an emotional and a rational level – it’s the study of textures and weaves, which symbolize integration. I started looking for naturally occurring textures without realizing how often I was doing it, then suddenly one day I became very aware – not only of what I was doing, but why.

I had reached a point in my life where it was becoming essential for me to integrate the multitude of experiences I’d had over the years all around the world. After coming to that realization, I deliberately set about learning how to create textures and weaves with my camera as well, for example by varying shutter speeds and by making multiple exposures. Concurrent with this has been the related on-going process of learning to see really large spaces as integrated wholes. Photography has become and remains for me a significant medium for dealing symbolically with the whole life process of self integration.

Beginning more recently, I have been exploring the unimaginably vast universe by means of ultra close-up and macro photography of back-lighted glass. On a window sill two metres from my computer are a wine glass (often with water in it), a plain paperweight, and a cut vase bowl. By focusing on highlighted imperfections in the glass, often picked up by the water as well, I enter a world that, by myself, I cannot imagine. I am only beginning to predict some of celestial visual phenomena I will encounter on this cosmic voyage, but what a trip it is!!!

And so is life.

No comments